This is the accurate and complete Q&A with Tim Reeves, following a correction to an editorial error in the print edition.

Spanning everything from bespoke residences to public housing and competition entries, the book features work by more than 70 architects (many designing their own homes), and includes over 300 images and floor plans drawn from archives across the state.

Tim Reeves tells us how he chose the homes, what makes Adelaide’s modernism so distinctive, and why the style continues to resonate with architects and homeowners alike.

Adelaide Modernism: 101 Houses covers a diverse range of modernist houses, from bespoke residences to blocks of flats and public housing. How did you go about selecting the 101 houses to feature?

I composed three selection criteria relating to architectural significance, historical significance and reputational significance, which guided me. The first houses I included were the ones that are well-known in the modernist idiom – they’d been widely published and were highly regarded in architectural circles. But I also wanted to have as broad a cross-section of architects as possible, and so I spent some time at the State Library going through John Chappel’s weekly house column that he wrote for the Advertiser for over 15 years from 1954.

I also researched home magazines, architectural journals and other newspapers of the period, and found the houses of some architects who had been lost in the mists of time. Finally, because it was important the book be visually appealing, I decided that a house could only be included if there were good images (particularly soon after completion) and floor plans. I’m proud to say that there are over 300 of these, many from the John Chappel archive at the State Library, and also from the Architecture Museum at the University of South Australia.

Many of the architects featured in the book lived in the homes they designed. How do you think this personal connection influenced their work and the final designs?

Of the more than 70 architects featured, nearly half are of their own house. And they include some of South Australia’s leading practitioners, like John Chappel, Jack Cheesman, Brian Claridge, Bob Dickson, Russell Ellis, Jack Hobbs McConnell, Newell Platten and Geoff Shedley, to name just a few.

I think it’s a reasonable assumption that you would expect an architect to be doing their very best work on their own house, especially if the final product could be used as a marketing tool to attract more clients. So, a lot of these houses were published in newspapers, magazines and newspapers: McConnell was a very savvy promoter in this regard. It was also an opportunity to trial new design ideas, building materials or other concepts. Keith Neighbour, for example, added steel cable cross-bracing to his house to strengthen it after the 1954 earthquake that hit Adelaide and caused £17 million of damage.

Adelaide’s modernist architecture spans over 35 years, from 1939 to 1974. How did the style evolve over this period, and what were some of the key design shifts you noticed during your research?

Although the first house in the book is dated 1939, there were earlier modernist houses that ultimately didn’t make the cut. That first house is interesting in that it was designed for a woman artist, and architect Russell Ellis gave her a first-floor studio which opened to a vast roof terrace with panoramic views of the city and sea. This terrace was formed from the flat roof covering the ground floor rooms, so it’s an early example of flat-roof design which would become ubiquitous in modernist houses.

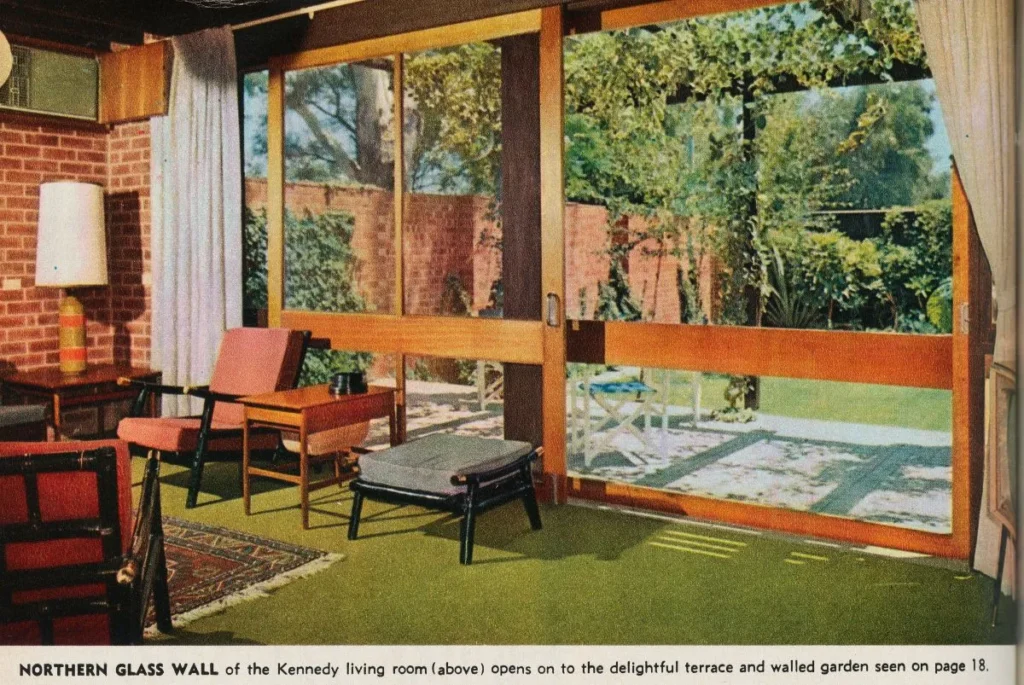

Another important design change was the opening up of interior spaces so that the living and dining rooms, and kitchen, were no longer shut off from each other. Houses also started to be oriented to the north with deep eaves to shut out summer sun but welcome winter sun.

Window walls not only drew in light and views but also allowed for indoor/outdoor flow, and promoted cross-ventilation. Garages started to become attached to houses when they used to sit at the back of a block, and over time carports became a very popular alternative. Houses also started to expand as family rooms, ensuites and the like became more mainstream.

Modernism was a global movement, but it took on a unique character in Australia. What aspects of modernist design do you think were particularly suited to Adelaide’s landscape and climate?

Adelaide, of course, is notorious for its dry and at times oppressively hot summers. But some local architects were convinced that a house built for arid conditions should be entirely liveable without mechanical assistance, although many people wouldn’t agree with that today!

One concept that arose was to design the living quarters in a wing of brick or stone that would heat slowly, but then to place the sleeping quarters in timber, so that they would be cooled by night-time gully breezes. Or to build entirely in wood, as South Australia’s first woman architect Marjorie Simpson did.

Allied to this, as previously mentioned, was to have windows on opposite walls to encourage cross-ventilation. Eaves were also used to control the sun, although the Badger House of 1958 had no eaves but used heat-resistant glass for its windows specially imported from Germany. Still, it was one of the first houses in Adelaide to incorporate ducted air-conditioning.

In your opinion, what makes modernist architecture still relevant and inspiring today, especially for those looking to build or renovate in a modern style?

I know from personal experience that good modernist architecture is inspiring and nurturing for the soul. I am fortunate to live and work in a modernist building that combines functional planning and rational aesthetics. This building is more than 80 years old but still completely relevant; it has so many lessons for those wishing to embrace modernist design today, whether in a new build or through renovation. There are so many elements, but if I could nominate just one it would be the utilisation of space. That is, how to use space more efficiently and openly, how to create light, bright and hygienic surroundings, and how to merge the indoors with the outdoors.

Many modernist houses in Adelaide have been preserved and even repurposed over the years. How do you think these houses contribute to the city’s current identity, and what role does preservation play in their legacy?

It is a delight to drive around Adelaide’s suburbs and see the many modernist houses of the 1930s to 1970s still standing. However, many have been poorly maintained or had extensions and/or renovations that are incompatible with the original design aesthetic. Even more distressing is the number of modernist houses that have been razed for multi-dwelling developments, or been replaced by a faux French chateau or neo-Georgian mansion. There is only a small number of houses in the book that have been maintained in almost original condition. These houses are absolutely crucial to the city’s identity and, as I argue in the introduction, it is time for local councils and the State Government to act to save what little there is left of our modernist heritage.

Were there any specific architects or projects in Adelaide that you found particularly groundbreaking or reflective of the unique local culture during the modernist period?

Where to start! What is delightful about the book is that many of the houses represented, especially in the early period, were so advanced in the way they used new technologies, materials, architectural forms and ways of conceiving space. As well as formulating ways to tame the climate for the comfort of the residents. I feel, even in some small way, each house in the book was groundbreaking. As well, Adelaide architects were producing modernist residential architecture that was easily on par with the eastern states, including Melbourne and Sydney. This is something of which Adelaide justly can be proud.

Lastly, given Adelaide’s unique position in Australia’s architectural landscape, do you see any signs of a modernist revival in the city’s current architectural projects, or is there a growing interest in this style again?

Modernism – also understood as mid-century modernism or MCM – has had an extraordinary renaissance around the world over the last few decades. Not just in architecture but also interior and industrial design. People in Australia are as much interested in MCM furniture and art as they are in house design. But due to financial reasons, many people who are wanting to build today – in Adelaide and elsewhere – have no choice but to approach a project home company and select from a stock of standard floor plans. The result can be a house too large for its lot, not properly oriented and with a dark roof which just sucks in the summer sun. You need good architects to design good architecture, but planning and building a bespoke house does not come cheap.

Adelaide Modernism, 101 Houses, Published by Wakefield Press, RRP $80.00